What would Don Draper do if he landed the Aunt Jemima account?

What would Don Draper do if he landed the Aunt Jemima account?

Now that Mad Men has completed its current season, I am left with one lingering question:

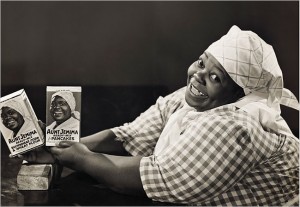

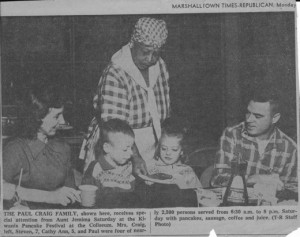

If you know about my book, “The Grace of Silence” then you know why I would ponder this question. I set out to write a book about America’s hidden conversations about race and wound up writing an accidental memoir when I started to listen to the hidden conversation about race among the people I love and realized that the elders in my family kept profound secrets locked away. Among them, was the discovery that my Grandmother had spent years in the late forties and early fifties working as a traveling Aunt Jemima selling pancake mix to midwestern farm wives, dressed up in a hoop skirt and head scarf. My mother never talked about my Grandma Ione’s work because it caused shame. Once I learned about this period in her life, I dug in to learn as much as I could about her stint working as an itinerant Aunt Jemima for Quaker Oats.

I also examined how the Aunt Jemima icon was created and nurtured over time by a series of ad executives who built a massive commercial campaign around a image rooted in slavery and contented submission. I have learned that ad executives have long struggled with the effort to update the brand’s history but hold onto the image. No wonder they went through so many contortions. The formula for updating a popular brand usually calls for updating the image while holding on to the brand’s rich history. But in this case Aunt Jemima’s history is so richly controversial that it still produces indigestion.

So my ears perked up during last week’s episode of Mad Men when Harry Crane — who heads the media department at the fictional Sterling, Cooper, Draper, Pryce ad agency, rattled off the name Aunt Jemima while ticking through a wish list of potential clients that could help the agency avoid total collapse. “Oh Lord,” I thought. Imagine if that crowd got their hands on that account. I don’t even want to think about the quips from Roger Sterling, Pete Campbell or Ken Cosgrove. How would Don Draper work his zen magic to come up with a concept for updating an ad campaign that featured a happy slave talking about how her “Happyfying Aunt Jemima Pancakes…. Sho’ sets folks singing!”

After discovering my grandmother’s work as a traveling Aunt Jemima I poured over these ads as I tried to understand her work, and her decision to do that kind of work.

I was fortunate enough to find something else in the archives. I got my hands on newspaper clippings about her travels to small towns and in these stories I learned that Grandma Ione portrayed a version of Aunt Jemima that was altogether different than the woman you might encounter in full-page ads that ran in magazines like Saturday Review and Ladies Home Journal.

She refused to speak in the slave patois used in all that advertising copy. She told reporters how she would work hard to leave a favorable impression on small town residents who had never seen a “Negro” woman before. For her, that meant letting those small town folk know she was educated. She spoke with her perfectly clipped diction. She would sing gospel songs so they would know she was a church woman. I don’t know what kind of hard bargain she made with herself when she pulled on that headscarf or hiked up her hoop skirt, but thanks to the newspaper clipping I do know she portrayed a difficult role on her own terms. I doubt she walked into those county fairs and small town grocery stores yelling Aunt Jemima’s signature catch phrase, “I’se in town honey!!!!”

By 1965, the year in which the current season of Mad Men takes place, the Quaker Oats company was under pressure by the NAACP and other groups to dispense of its happy slave logo. The protestations continue to this day, as petitioners make a persuasive argument that “No black woman in America is safe from the cruel and disrespectful hurt of the image and history of Aunt Jemima.” (Though Aunt Jemima’s corporate makeover has transformed the woman on the pancake box into a prim, grey-haired maven that looks like she might teach a home ec class, the upgrade has not uprooted the stigma. If you don’t believe me, just try to lovingly call a black woman — any black woman –Aunt Jemima)

By 1965, the year in which the current season of Mad Men takes place, the Quaker Oats company was under pressure by the NAACP and other groups to dispense of its happy slave logo. The protestations continue to this day, as petitioners make a persuasive argument that “No black woman in America is safe from the cruel and disrespectful hurt of the image and history of Aunt Jemima.” (Though Aunt Jemima’s corporate makeover has transformed the woman on the pancake box into a prim, grey-haired maven that looks like she might teach a home ec class, the upgrade has not uprooted the stigma. If you don’t believe me, just try to lovingly call a black woman — any black woman –Aunt Jemima)

The criticism about the decades-old logo is almost always focused on the image of Aunt Jemima. Though she now wears pearls and a grey-flecked, wet-set hairdo, she still sits in the critic’s cross hairs. However, the people who created that image remain largely out of view: The proverbial hands that rock the cradle… or in this case silently count the money as the Aunt Jemima brand continues to rack up sales.

The wistful yearning of a bespectacled actor on Mad Men who is so eager to get a shot at winning the Aunt Jemima account helped put a face on the other side of the advertising equation. I shudder to think of the pitch Don Draper would settle on if he did win the account. And just imagine the cynical banter in the art department before the creative team settled on a pithy pitch. It would likely turn your stomach or make your hair stand on end. Perhaps it would do both. Or, perhaps the progressively-minded Peggy Olson, the only woman with a voice at most of these pitch sessions, would step up and let the guys have a piece of her mind. It’s the best one could hope for on a show where Sterling, Cooper, Draper and Pryce occupies a strange slice of New York City where people of color simply do not exist except in occasional cameos pushing a floor waxer or a sandwich cart.

There is Carla, the maid who watches Don and Betty’s three children. Or I should say she watched their children because Betty bumped her off the job with a flourish of cruelty that would have made Bette Davis cringe. No chance to say goodbye to the children she had cared for since their birth. No letter of recommendation. It is fairly certain that Carla won’t appear in next season’s run since she is not even listed among the cast and crew for the current season. A list that by the way includes several minor characters who have amassed far less screen time.

There is Carla, the maid who watches Don and Betty’s three children. Or I should say she watched their children because Betty bumped her off the job with a flourish of cruelty that would have made Bette Davis cringe. No chance to say goodbye to the children she had cared for since their birth. No letter of recommendation. It is fairly certain that Carla won’t appear in next season’s run since she is not even listed among the cast and crew for the current season. A list that by the way includes several minor characters who have amassed far less screen time.

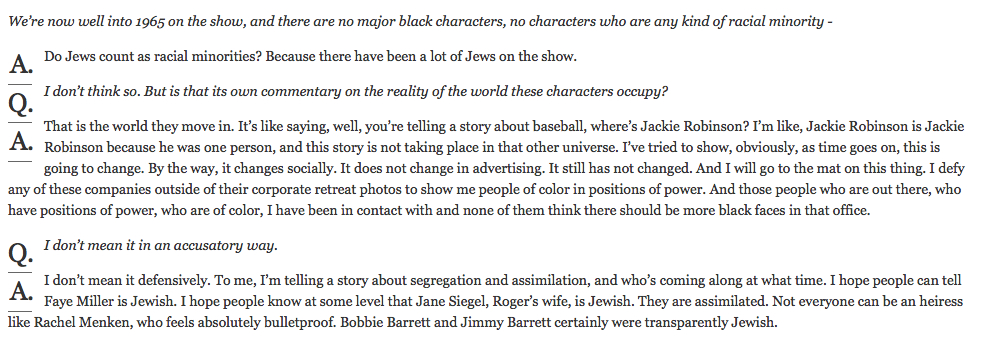

In yesterday’s New York Times, Mad Men Executive Producer Matthew Weiner explains in a Q & A that the dearth of black faces in perhaps the most diverse city in the world is explained by the insular nature of a high-flying advertising firm. “This is the world they move in,” he told the interview Dave Itzkoff. Here is the full exchange:

I have been a loyal viewer of Mad Men since season one. I plan my Sunday evenings around the broadcast. So many aspects of the show are brilliant. This is not one of them and Weiner is too smart a fellow to try to get away with such a a weak excuse for his failure to cast a wider net in terms of casting and story line. To be sure, black or Latino women would not likely be sipping coffee or adjusting their girdles with the rest of the gals in the secretarial pool at Sterling Cooper in 1965. Similarly, black executives would not likely be sitting around the conference table throwing back gimlets with Don and his merry band of workday lushes. But an ad agency that prides itself on tapping into the zeitgeist of American culture would not be so blind to the seismic changes happening just outside their doors. And a show that winks at the audience by salting the show with genuine cultural references from the era has a curious blind spot.

The music, the clothes, the product placement and the prodigious use of plaid are all spot on. When the producers combed through the mid-sixties sociological archives they failed to notice or set aside any reference to the explosion of black culture in America. How can a firm hawk Clearasil and fail to notice the Motown acts on American Bandstand? Wouldn’t a cutting-edge firm that aspires to be Manhattan cool and Hollywood hip have noticed Sidney Poitier’s historic Best Actor Oscar for the film, Lilies of The Field — a moment that was applauded around the world?

The music, the clothes, the product placement and the prodigious use of plaid are all spot on. When the producers combed through the mid-sixties sociological archives they failed to notice or set aside any reference to the explosion of black culture in America. How can a firm hawk Clearasil and fail to notice the Motown acts on American Bandstand? Wouldn’t a cutting-edge firm that aspires to be Manhattan cool and Hollywood hip have noticed Sidney Poitier’s historic Best Actor Oscar for the film, Lilies of The Field — a moment that was applauded around the world?

I can only conclude that the black-out on the show is a result of a lazy worldview, creative snobbery and a writing staff that pats itself on the back for diversity if east coast and west coast viewpoints are represented, or if the chorus includes voices from the reformed and orthodox camp.

For months I have been downplaying my husband Broderick’s dismissal of the show as racially offensive. “Why would I want to watch a show that tries to wish me out of existence,” is his essential argument. I gave Weiner some room on this one. He struck out when Itzkoff lobbed an easy pitch across the plate. Too bad.

Another reason this really bugs me is that the people in my parent’s generation were also on the bumpy road to something approaching assimilation in America and the ads that agencies like Sterling Cooper churned out often served as their guide. Drink This. Drive that. Wear those. The Mad Men of that day may have ignored people of color but they sure weren’t willing to ignore the green stuff in their wallets. Vintage Ebony and Jet magazines are filled with slick ads for booze, cars, cigarettes, food, and medicine – ads no doubt produced my the Mad Men of that era.

In today’s world, the TV ads are often more diverse than the shows they’re wrapped around. A virtual rainbow of actors sell everything from retirement plans to Raisin Bran. The real Mad Men woke up and smelled the opportunity. It’s time for the people behind the fictional Mad Men to wake up too.

-Michele

Michele Norris is a Peabody Award-winning host and Special Correspondent at NPR. She produces in-depth profiles, interviews and series for NPR News programs. Norris also leads The Race Card Project, an initiative to foster a wider conversation about race in America that she created after the publication of her family memoir, The Grace of Silence. For more than a decade, Norris was a host on NPR’s “All Things Considered” where she interviewed world leaders, American presidents, Nobel laureates, leading thinkers and groundbreaking artists. Norris is also a Shorenstein Fellow at The Harvard Kennedy School.

Michele Norris is a Peabody Award-winning host and Special Correspondent at NPR. She produces in-depth profiles, interviews and series for NPR News programs. Norris also leads The Race Card Project, an initiative to foster a wider conversation about race in America that she created after the publication of her family memoir, The Grace of Silence. For more than a decade, Norris was a host on NPR’s “All Things Considered” where she interviewed world leaders, American presidents, Nobel laureates, leading thinkers and groundbreaking artists. Norris is also a Shorenstein Fellow at The Harvard Kennedy School.

You can find, The Grace of Silence, at your local book store or you can order it online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Borders, Powell’s or IndieBound